Comparing “Consent” Rules in General Data Protection Laws across Asia-Pacific

Recent years have seen a massive transformation of the data protection landscape in the Asia-Pacific, with many major jurisdictions enacting, reviewing, or preparing comprehensive data protection laws1. Josh Lee Kok Thong, Managing Director (APAC) of the Future of Privacy Forum (FPF)’s Asia-Pacific office, shares key takeaways from a year-long comparative review by FPF and the Asian Business Law Institute (ABLI) on the topic of “Consent” across Asia-Pacific.

Consent: A common denominator with common challenges

One core area of interest for regional compliance is consent requirements and other legal bases for processing personal data.

Consent as a legal basis is a common denominator across the Asia-Pacific. In fact, based on FPF’s recent comparative review2 of 14 major Asia-Pacific data protection regimes, consent is the only legal basis that is shared by all regimes and that applies to processing all forms of personal data (including sensitive data).

However, Asia-Pacific jurisdictions are increasingly recognising the challenges of over-relying on consent. These include increased compliance burdens from the significant divergence in the conditions for valid consent (e.g., that consent must be explicit, informed, voluntary, recorded / in writing, etc.) across regional data protection laws. In fact FPF’s review found that no single condition is shared equally by all of the jurisdictions studied. Additionally, an over-reliance on consent may cause consumers to experience “consent fatigue” where, faced with an information overload from privacy policies and notices, they simply consent to processing of their personal data without fully comprehending the implications of their decisions.

These, among other reasons, are why jurisdictions have begun considering the need to reframe consent. For instance:

- In 2020, Singapore shifted its data protection regime from a primarily consent-based framework to one permitting collection, use, and disclosure of personal data without consent in a wide range of situations, including “vital interests of individuals,” “matters affecting the public,” “legitimate interests,” “business asset transactions,” “business improvement purposes,” and“research.”Since November 2021, Chinese regulators have sought to restrain “bundled consent” in baseline texts like the Personal Information Security Specification or in the Personal Information Protection Law.

- Since 2020, Australia has been undertaking a sweeping review of its Privacy Act, including consent requirements.

These developments represent a window of opportunity to enhance the compatibility of regional data protection laws. The next section turns to the regional picture on alternative legal bases to consent.

Alternative legal bases to consent

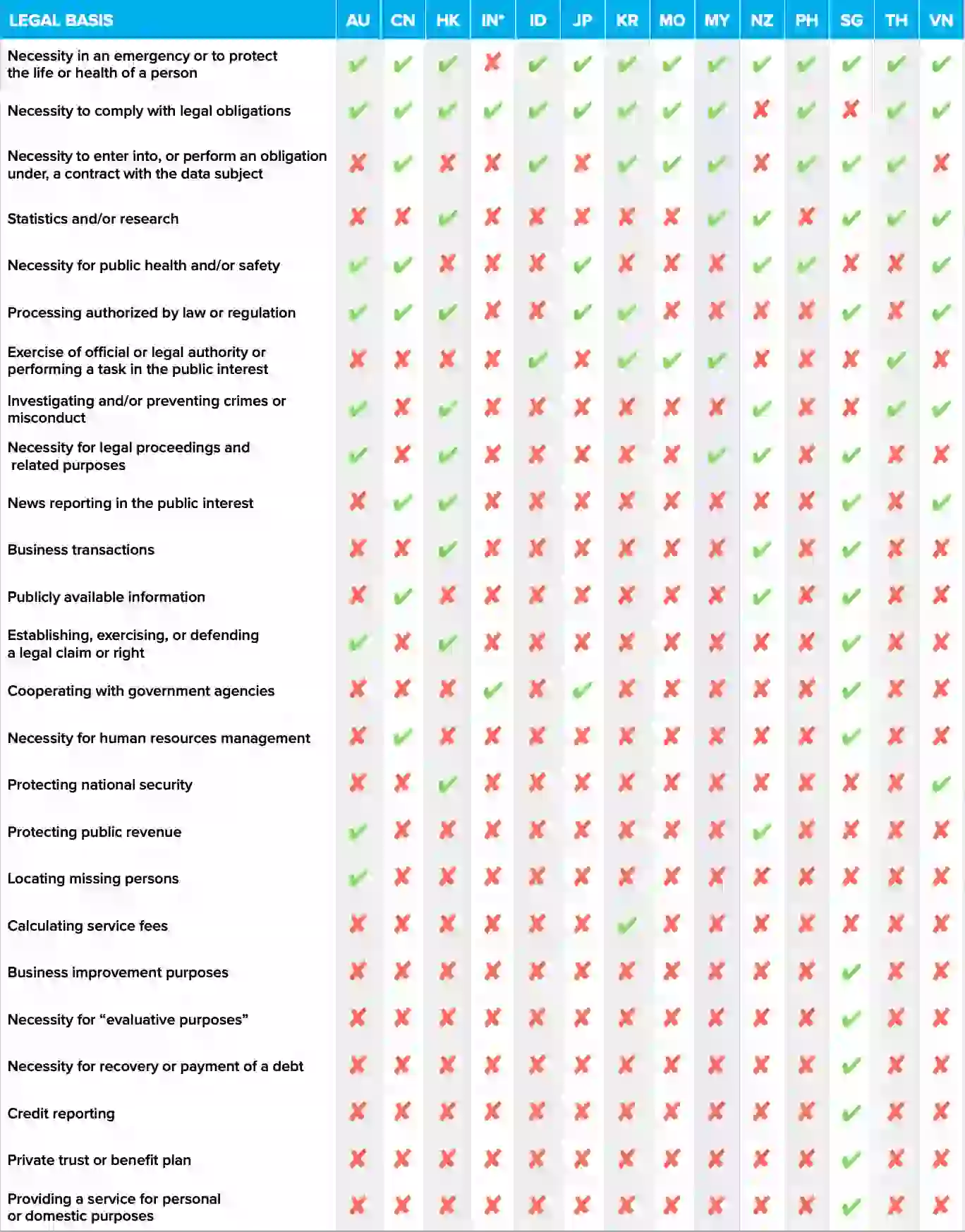

From FPF’s review, all 14 jurisdictions3 provide alternative legal bases to consent for processing personal data. FPF’s review identified 26 such bases, which are outlined in Table 1 below.

Table 1: An overview of alternative legal bases to consent for processing personal data in the data protection laws of 14 jurisdictions in the Asia-Pacific

Yet, behind this superficial commonality is significant diversity. Several observations may be made:

- Singapore recognises (by far) the most such bases. Indonesia, Japan, Macau SAR, and the Philippines recognize the fewest such bases. India’s existing data protection framework only recognizes a single such basis; however, this will change when the newly-enacted Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023 (DPDPA) takes effect4 as the DPDPA sets out nine “legitimate uses” of personal data, where consent is not required.

- All 14 jurisdictions permit processing of personal data without consent where necessary to protect the life or health of a person. Further, most jurisdictions (except New Zealand and Singapore) recognise a general legal basis for processing personal data where necessary to comply with a legal obligation.

- Approximately half of the jurisdictions provide legal bases to process personal data without consent where necessary for entering into or performing obligations under a contract, or for statistics and/or research.

- A third of the legal bases are unique to a single jurisdiction. While some of these bases could be covered by broader legal bases elsewhere (e.g. jurisdictions which do not expressly recognise a legal basis for protecting public revenue may nonetheless permit processing of personal data without consent to perform a task in the public interest), the lack of clarity increases the complexity and cost of cross-border compliance.

While these bases play a useful role, their value as an alternative to consent may be limited as they can only be used in specific circumstances. By contrast, another legal basis – legitimate interests– has great potential as an alternative to consent that can be used in a much wider range of circumstances. We turn next to the regional picture for this legal basis (and similar bases).

Legitimate interests (LI)

In FPF’s review, data protection laws in 10 of the 14 studied jurisdictions either have an express LI basis for processing personal data without consent, or a similar basis that is broadly compatible with a LI basis. Importantly, these provisions are open-ended and flexible enough that potentially any “legitimate interest” could be taken into account. However, there are still considerable differences in how the provisions are drafted or structured, which could increase compliance costs for businesses operating across borders. Several observations may be made:

- 6 of the jurisdictions studied (Indonesia, Macau SAR, the Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, and Thailand) have a clearly identifiable LI basis. These provisions (except Singapore’s) generally resemble their counterpart in the GDPR, although South Korea imposes a somewhat stricter balancing test5. Singapore’s provision has different requirements from its European equivalent and imposes a stricter balancing test6.

- The other 4 jurisdictions (Australia, Hong Kong SAR, Japan and New Zealand) have provisions that share many elements with the LI basis. In these jurisdictions, consent is not required where personal data is used for a lawful purpose that is connected with a business’s functions or activities7. While the requirements are less comprehensive than the balancing tests in the European and Singaporean formulations, they involve many of the same considerations, like necessity, lawfulness, and fairness.

- The remaining 4 jurisdictions (China, India, Malaysia, and Vietnam) presently lack a LI basis. Notably, India’s recently-enacted DPDPA also lacks a LI basis.

In sum, while the LI basis presents an opportunity for interoperability across jurisdictions in the region, small yet significant differences across these formulations present challenges for cross-border compliance. In this regard, the devil is indeed in the detail. The next section offers some points for reflection and recommendations for regulators and practitioners.

Reflections and recommendations

While there are many potential areas for convergence or interoperability of data protection laws in Asia-Pacific, there are clearly also distinct divergences. These divergences affect interoperability, create legal uncertainty and compliance challenges for organisations operating in the region, and exacerbate concerns such as “consent fatigue.”

Yet, despite differences in cultural norms and variations in regulatory models, Asia-Pacific jurisdictions share mutual interests in bridging gaps between data protection frameworks and reducing legal uncertainty. For organisations, doing so facilitates cross-border compliance and avoids unnecessary duplication of compliance efforts – advantageous for the region’s small and medium enterprises and start-ups. For regulators, it would create common ground for regulatory cooperation, consistent regulatory action, and better integration with global standards and other regional frameworks.

While the Asia-Pacific region continues to find its way towards greater coherence and interoperability, data protection officers (DPOs) and practitioners can play their part by exploring appropriate use cases to integrate alternative legal basis to consent, such as the LI basis, into their cross-border compliance programmes, as well as encouraging their organisations to use different mechanisms that facilitate the processing of data across borders, such as the ASEAN Model Contractual Clauses and global certification systems, such as the Global Cross Border Privacy Rules System (CBPR).

A set of recommendations for DPOs and regulators to help increase interoperability and convergence of legal bases for processing personal data at an ecosystem-wide level is summarised in Table 2 below.

Table 2: Summary of recommendations from FPF’s comparative review

|

Aspect |

Summary of recommendations |

|

Consent |

|

|

Alternative legal bases |

|

|

LI basis |

|

Consent and alternative legal bases to processing data, including the LI basis, all have their place in a robust, effective, and well-balanced data protection regime. Privacy and data protection, like all other fields of regulation and human endeavour, however, must not forget the human factor. Overreliance on consent as a heuristic to seek data protection compliance has generated a myriad of issues and challenges. While this is not the fault of any one player, the onus is on all players in the ecosystem to find potential solutions. FPF hopes that this article and the review it summarises can spark deeper thought and discussion within the DPO community on how to re-balance individuals’ and organisations’ interests in data protection.

Article contributed by Josh Lee Kok Thong, Managing Director (APAC), Future of Privacy Forum

Disclaimer: The contents of this article and the FPF Report are written to the best of the material and information available to us. While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, the author and FPF disclaim all liability and responsibility for the consequence of any reliance placed, whether wholly or partially, on this article or the FPF Report. Nothing in this article should also be construed as legal advice. If you require legal assistance on any of the topics covered above, you are encouraged to engage a local lawyer.

1 E.g., China, Thailand, Indonesia, Australia, India, Vietnam, Japan.

2 The FPF’s APAC office and the ABLI, embarked on a year-long comparative review of data protection regimes – in particular, on consent regimes and alternative legal bases to process personal data across 14 jurisdictions - seeking to initiate a dialogue on differences and commonalities among the rules establishing lawful grounds for processing personal data under the general data protection laws in the region, as well as on opportunities for their interoperability.

3 Australia, China, India, Indonesia, Hong Kong SAR, Japan, Macau SAR, Malaysia, New Zealand, the Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, Thailand, and Vietnam.

4 Note that the Digital Personal Data Protection Act does not specify a date when it will take effect. Rather, the Act empowers the Indian Government to determine the dates on which different sections of the Act will come into force.

5 Specifically, South Korea’s LI basis requires the legitimate interest of the controller to “clearly override” the rights of the data subjects. Other additional requirements include the fact that the processing of personal data under the LI basis can only be to the extent that the processing substantially relates to the legitimate interest, and is also within a reasonable scope.

6 Specifically, Singapore’s formulation of the LI basis lacks a necessity requirement (compared to its European equivalent). Its balancing test is also different in that the interest relied upon must “outweigh any adverse effect on the individual”. Singapore’s LI basis also requires organisations to undertake a data protection impact assessment (DPIA) to identify and implement measures to address adverse impacts on individuals.

7For Australia and Japan, this exception is available only for personal data other than sensitive personal data.